FORDHAM FORENSICS When It Really Matters770-777-2090

FORDHAM FORENSICS When It Really Matters770-777-2090

Contents

- E-discovery Costs by Task

- E-discovery Costs by Source

- Matrix of E-discovery Costs by Task and Source

Inquiries

The Firm of Fordham Forensics in Atlanta, GA

is a highly skilled and experienced provider of

e-discovery services including ESI identification, preservation, data processing and production, search, hosting, discovery planning and

consulting services.

To learn more about electronic discovery or

discuss a specific matter

770-777-2090

E-Mail

Related Articles

Finding & Selecting A

Computer Forensic Expert

Computerized Search &

Other Digital Litigation Strategies

Designing an E-discovery Protocol

Protecting Privilege from Inadvertent Disclosure in E-Discovery

Selecting an E-Discovery Vendor or Consultant:

A Best Value Approach

Gregory L Fordham

(Last updated December 2015)

Those familiar with Electronically Stored Information in general and e-discovery in particular know that it has a long history that predates the 2006 changes to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP). For example, the case of Bills v Kennecott Corp., 108 F.R.D. 459, 461 (D. Utah 1985) not only used the term ESI 20 years before the 2006 changes to the federal rules it also stated that, “It is now axiomatic that electronically stored information is discoverable under Rule 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. . . .” Similarly, in the case of Anti-Monopoly Inc. v Hasbro, Not Reported in F.Supp., 1995 WL 649934 (S.D.N.Y.) it was stated more than a decade prior to the 2006 changes that the discovery of computerized data was now “black letter law”.

Another commonly misunderstood aspect of e-discovery is its costs. Since the widespread use of computerized data in litigation, many have claimed that e-discovery is expensive and is causing cases to settle based on discovery economics and not based on their merits. As a result, many have avoided e-discovery despite that they are likely hurting their cases since about 98 percent of available data is in digital form.

While the claims that e-discovery is expensive may be true, what few realize is that the true cause for the high cost of e-discovery is not the nature of the digital evidence, the inherent procedures and processes related to the digital evidence or the use of vendors and consultants who are experts with digital data. Rather, it is the inefficient and very costly methods employed by the very people who have managed and directed the use of e-discovery in litigation, which are lawyers and law firms. In fact, studies show that outside counsel will consume 70 percent of the costs for producing ESI and that does not include other costs of the litigation like motion practice, summary judgment, mediation, other experts, pre-trial hearings or the trial itself. Furthermore, they do not even include other aspects of discovery like depositions, resolving discovery disputes, or attending the discovery conference or scheduling conference.

The truth is that e-discovery can be more effective and more economical than traditional paper based discovery. In fact, the reality is that e-discovery is the big equalizer. No longer is victory determined by the side having the largest army of associates or even the deepest pockets but the one that can best use their technology to defeat their opponent in the courtroom. Unfortunately for many, they have have been using their technology more like a club than like a machine gun and at great expense to their clients.

A significant cause for the high cost of e-discovery has been a preference for using manual document review techniques to determine which documents are responsive and relevant as well as which documents should be withheld for privilege or require special handling because of sensitive information. Of course, manual document review techniques are well known. They are what has been used since well before the existence of digital evidence. The problem is that these archaic methods are also very costly, very inefficient and very ineffective as well. Thus, there is nothing to be gained by using them when solving the disclosure problem for ESI.

In the sections that follow the consequence of manual document review are examined as reported in a 2012 report released by the Rand Corp. The results explain quite a lot about the true cause for the high cost of e-discovery.

Where the Money Goes

It is often said that a consequence of the digital age on litigation is the large volume of data that is available for discovery. Remarkably, the review of this information in response to an opponent’s document production request is still largely performed by archaic manual document review techniques that were developed in a bygone era. This very point was confirmed in a 2012 report produced by the Rand Corporation’s Institute for Civil Justice, which is a research institute within its Law Business and Regulation research division. The report was titled, Where the Money Goes: Understanding Litigant Expenditures for Producing Electronic Discovery. It is commonly referred to as the “Rand Report”.

The study examined the costs of producing ESI in 57 litigation matters involving "traditional lawsuits and regulatory investigations". The distribution of the cases involved federal and state courts as well as commercial arbitrations and regulatory investigations. The actual breakdown of the cases between those categories is shown below.

FORUM |

CASES |

|

Federal Court |

36 |

|

State Court |

9 |

|

Regulatory Investigation |

11 |

|

Commercial Arbitration |

1 |

|

|

|

|

The breakout of the cases by subject matter was also diverse and is shown below.

| SUBJECT MATTER | CASES |

|

Antitrust |

2 |

|

Contract |

8 |

|

Employment |

1 |

|

Environmental |

1 |

|

Fraud or False Claims |

4 |

|

Insurance |

2 |

|

Intellectual Property |

18 |

|

Product Liability |

7 |

|

Real Property |

1 |

|

Regulatory Investigation |

11 |

|

Unfair Trade Practices |

2 |

|

|

|

|

The total production costs of each case studied ranged from just over 17,100 dollars on an intellectual property matter to over 8 million dollars on a product liability case after excluding two product liability cases whose costs were over 20 million dollars each. The median value of e-discovery production costs for all the cases studied after omitting the two outliers was around 1.9 million dollars.

The dollars at stake in the cases ranged from 2 million to 400 million dollars. These values are on the high side of many litigation matters that are more typically less than 1 million dollars. While the dollars at stake and costs for each case studied may be above average, there is no reason to believe that the cost trends as a percentage or on a gigabyte basis would not apply to cases of all sizes.

Since the study focused on the cost of producing ESI, it did not consider the costs from other aspects of the litigation lifecycle like motion practice, summary judgment, mediation, other experts or trial itself. In fact, it did not even consider all aspects of discovery like attending the 26(f) discovery conference or depositions. Rather, it focused solely on those aspects of discovery related to the production of ESI.

The report provides some interesting results related to the cost of producing ESI by task and by source. The following sections examine those results.

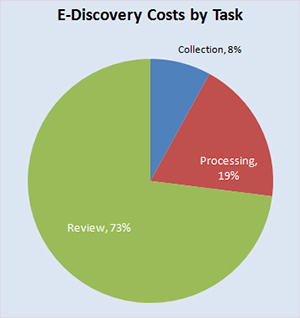

Costs of Production by Tasks

One of the first ways that the report presented its findings was the breakdown of e-discovery costs between the three tasks of collection, processing and document review. This data appears in Figure S1 on page XV of the report and is reproduced in the chart below.

The three categories in which costs were accumulated for the study were developed and correlated to the nine categories appearing in the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM). The study defined its three categories as follows.

- Collection was defined as, “ . . . [L]locating potential sources of ESI following the receipt of a demand to produce electronic documents and data, and gathering ESI for further use in the e-discovery process, such as processing or review.” Thus the collection phase included both identification and preservation of ESI while maintaining data integrity and chain of custody. It also would have involved preservation under either forensic grade imaging or targeted data collection. The collection phase excluded and the EDRM category known as Information Management (IM). In the EDRM, IM is the processes and systems used to by an organization to manage its ESI on a daily basis and mitigate the costs of e-discovery should it occur. Document retention and destruction policies are examples of an organization’s IM processes used to manage ESI on a daily basis and mitigate the costs of e-discovery should it occur.

- Processing was defined as, “ . . . [R]educing the volume of collected ESI through automated processing techniques, modifying it if necessary to forms more suitable for review, analysis, and other tasks.” The processing phase not only included the actual efforts for volume reduction and converting the data to a form more suitable for review but also the incidental costs related to those efforts such as data hosting costs and delivering the final product to opposing parties.

- Review was defined as, “ . . . [E]valuating digital information to identify relevant and responsive documents to produce, and privileged documents or confidential or sensitive information to withhold.” It also included costs to, “ . . . [D]ocument and inform opposing counsel about the decisions made regarding privilege or highly sensitive information”. The review process is also often used to gain a greater understanding of the factual issues in the case, identify key documents in the population and develop legal strategies. Those costs were included as well.

According to the study, collection, which comes first in the ESI production process, is remarkably only 8 percent. As indicated previously, the collection phase not only includes the actual collection and preservation but the identification of ESI as well. Thus, it is not just the preservation effort done by forensic imaging experts. Clearly, that effort would be even less.

According to the study, collection, which comes first in the ESI production process, is remarkably only 8 percent. As indicated previously, the collection phase not only includes the actual collection and preservation but the identification of ESI as well. Thus, it is not just the preservation effort done by forensic imaging experts. Clearly, that effort would be even less.

The collection phase is the most sweeping of the e-discovery efforts since not all of the data collected is ever produced or even considered for production, particularly where the data is highly duplicative like with backup tapes or overly inclusive like with custodians having a very minimal connection to the issues of interest. Also, in a multi-stage discovery plan, items that were collected may never make it to production or the costs could be more than their expected benefits.

Perhaps because it is the first cost incurred during ESI production and one of the tasks that is typically performed by vendors and not counsel, the collection phase has received considerable attention by policy makers and the profession. In fact, a lot of the early case decisions involved preservation issues. In addition, a lot has been written by organizations like the Sedona Conference. These writings were designed to reduce both the costs and the burden of collection in particular and e-discovery in general. There has even been a move away from forensic grade imaging to targeted data collections in an effort to reduce collection costs and overall e-discovery costs.

At only 8 percent, however, the cost of collection is a trivial portion of the total discovery costs when compared to the other tasks that will follow, particularly document review that is over 70 percent. Thus, not only is the amount trivially small when compared to processing or document review, there is not much room for realizing meaningful cost saving benefits if cost saving measures could be employed. Clearly, one will not make e-discovery any more affordable by finding more and more economical methods for identification, preservation and collection. There simply is not much there from the start.

In addition, the importance of the collection phase should not be underestimated. If done poorly, it can handicap or even fatally wound a party to litigation since key evidence could have been missed that cripples a party’s claims or preservation performed improperly that results in sanctions. A study published in the November 2011 Duke Law Journal that was titled, Sanctions for E-Discovery Violations: By the Numbers examined 401 sanction decisions from 1981 through 2009 and found that about 60 percent of all sanction awards involve preservation efforts.

The second task, processing, is 19 percent of the total ESI production cost. Processing is the next area that tends to get a lot of attention in an effort to cut e-discovery costs. At only 19 percent, however, cost savings opportunities are limited there as well. Furthermore, processing is where volume reduction occurs as well as other processes that can reduce the need for more expensive document review. Thus, trying to cut costs by reducing processing efforts can be counterproductive. In other words, needlessly reducing processing costs as a means to cut overall e-discovery costs can be like choosing a shovel to dig a ditch instead of using machinery like a backhoe. While the shovel may have a lower cost, the increased productivity of the backhoe will more than compensates for its increased cost. With respect to e-discovery processing in particular, if a 10 percent increase in processing costs could cut the cost of document review by 10 percent the overall cost of e-discovery would be reduced.

The third task, document review, is the most expensive and consumes about 73 percent of e-discovery costs. It is almost three times larger than the costs of collection and processing combined. If there is any area of the e-discovery process that is worthy of and an obvious target for expenditure reduction it is the document review phase. Clearly, e-discovery could be more palatable if the cost of this phase was more in line with both the collection and processing phases.

By digging deeper into the numbers in the report that are contained in Tables A-1 and A-2 in Appendix A along with the earlier data contained in Figure 2.1 in Chapter 2, one can calculate that the average cost of document review was more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte.

By digging deeper into the numbers in the report that are contained in Tables A-1 and A-2 in Appendix A along with the earlier data contained in Figure 2.1 in Chapter 2, one can calculate that the average cost of document review was more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte.

Although not reflected in the numbers themselves but discussed in the report narrative was that the high cost of review was the result of manually based review processes. A manual review cost of 15,000 dollars per gigabyte equates to between 45 and 75 dollars per labor hour using standard metrics of 50,000 to 75,000 pages per gigabyte and a manual review rate of 2,000 pages per day.

The pages per gigabyte metrics are subject to considerable fluctuation that depends on the type of documents in the population. For example, graphic images could have significantly fewer pages per gigabyte (like 10,000) while text documents could have a significantly higher number of pages per gigabyte (like over 100,000).

The hourly labor rate calculated above is all inclusive, too, and includes all markups, taxes and insurances. Thus, the raw labor hour rate is even less than 45 to 75 dollars per hour, which makes one wonder what kind of expertise is actually being purchased at that low of a labor rate?

While the cases may have employed cost saving measures like contract review attorneys or off-shore review attorneys, it was a manual process nonetheless. The report recognizes that manual review methods are very costly. In addition, they are inherently inefficient and ineffective. Furthermore, this fact is well known since it has been the focus of numerous studies over the years.

More specifically, Text Retrieval Conferences (TReC), as an example, have found recall rates (essentially relevance) of manual reviewers at around 59 percent while technology based methods had recall rates of 79 percent. Other studies, like those performed by Maura Grossman, have examined the overlap in the relevance determination made by different reviewers and found that the overlap or agreement between different reviewers is only 15 to 49 percent. Thus, the error rate in making a relevance determination was between 51 and 85 percent. The primary cause for this huge error rate is that relevancy is a highly subjective determination.

Precision and accuracy rates of manual review versus technology assisted review are no better. TReC has found the accuracy rate of manual reviewers at only 31 percent while the accuracy rate of technology based review at 84 percent on average. In fact, keyword search is the most accurate and has the highest precision ratings of all the technology based search methods. The drawback for keyword search is it can also have a low recall rate or relevancy result. A significant factor in the low recall rate for keyword search is the frequent use of simplistic search criteria. Thus, the recall rate of keyword search technology can be improved with better constructed keyword search criteria that have properly employed linguistics and advanced search features like Boolean operators, proximity locators, stemming, etc. in conjunction with proper prototyping and testing.

Not only are the manual review techniques less effective than technology assisted methods, they are more expensive, too. Manual review techniques are typically 20 to 40 times more expensive on a gigabyte basis than technology assisted review methods. Thus, while it might be hard to entirely avoid manual review techniques, they are not something one should choose as their primary solution to the document selection and disclosure problem.

In addition to the cost per gigabyte, one can also calculate that on average each case studied in the report contained more than 90 gigabytes of data for review but that only about 23 gigabytes were actually produced. Thus, almost 75 percent of the data subjected to review at more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte were not produced because they were either not responsive, not relevant or privileged and not subject to production.

Clearly, a situation where 75 percent of the data subject to final review is useless does not speak well for the preprocessing efforts that were used to reduce and screenout irrelevant documents. While the report does not address this issue, it is what happens when one focuses on minimizing vendor processing costs that typically range in the hundreds of dollars as compared to the thousands of dollars that the ultimate manual review will cost. Since the report quantifies the cost of processing as only 19 percent of the overall production costs, that likely is a clue that technology based processing capabilities along with preprocessing analytics were not on average effectively implemented for the cases studied.

Clearly, one must question the efficacy of spending an average of 15,000 per gigabyte on manual review when technology assisted review provides both greater economy and greater effectiveness. Even if for some reason manual review was desired there is ample reason for more effective use of volume reduction processing in order to reduce the final amount of data that will be subject to manual review in order to cut ESI production costs overall.

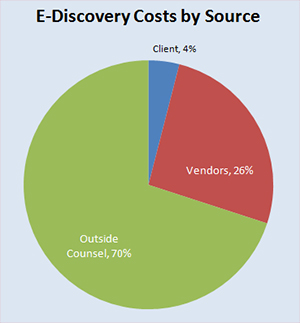

Cost of Production by Source

Another way that the study examined the cost of producing ESI was by the three sources of clients, vendors and outside counsel. The results of that review are presented in Figure S1 on page XV of the report and reproduced here in the chart below.

- The term client is being used in this writing. The report actually used the term “internal expenditures”. Internal expenditures included salaries and benefits paid to the organization’s employees, including attorneys, paralegals, and support staff in corporate law departments, as well as members of IT departments and other business units in which effort was expended to comply with e-discovery production requests. Costs associated with contract attorneys directly hired by the corporate legal departments as if they were employees were classified as internal expenditures. If they were not a direct hire but provided through an employment agency or service bureau they were treated as a vendor. In addition, purchase costs or licensing fees paid for computer applications and hardware primarily intended to assist in discovery requirements would included as an organization’s e-discovery costs.

- Vendors were defined as companies and individual consultants who offer one or more e-discovery–related services. Such vendors may be selected and managed by outside counsel, in-house counsel, other staff within the organization, or other vendors. Contract attorneys hired by outside counsel or clients were treated as vendors if they were a pass through cost and were not direct hires similar to other employees of the organization.

- Outside counsel includes any attorney or law firm retained by the organization to represent its interests. E-discovery expenses for outside counsel would include hourly billings or other fee arrangements; expenditures managed or controlled by outside counsel; the use of the firm’s IT infrastructure for hosting data; and use of the firm’s review-tool platform, travel, and other costs of litigation. The costs of contract attorneys were treated as a vendor if they were simply a pass through cost on the firm’s billings.

When the data are reviewed by source, clients account for only 4 percent of the production costs while vendors account for 26 percent. Amazingly outside counsel accounts for 70 percent of e-discovery production costs.

When the data are reviewed by source, clients account for only 4 percent of the production costs while vendors account for 26 percent. Amazingly outside counsel accounts for 70 percent of e-discovery production costs.

It is striking that vendors account for only 26 percent of the costs. Within e-discovery circles and legal practitioners there is constant chatter complaining about vendor costs. There are even seminars taught and articles written about how to better manage vendors but the numbers from the Rand Report indicate that they are only a quarter of the total e-discovery costs.

Clearly while it is nice to control all costs, the extreme focus on vendor costs is simply not sensible. The largest portion is counsel costs. Furthermore, counsel cost is nearly three times that of vendor costs. Counsel cost is the bigger target, therefore, and thus the one likely to have the biggest payoff. Thus, it would make more sense to focus cost saving efforts in that direction.

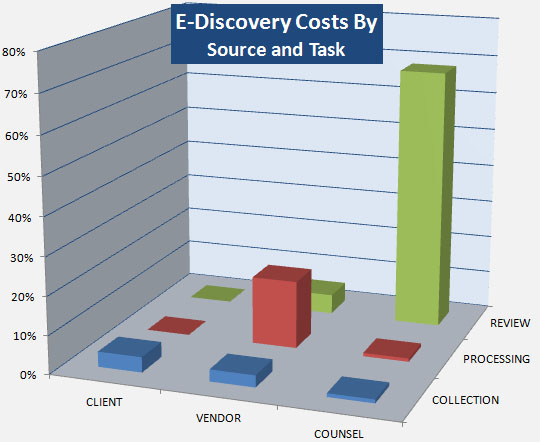

Matrix of Production Costs by Task and Source

One can take the data presented in Figure 1 on page XV of the report, and reproduced in the above charts, and combine it with the data in Table 1 on page XV of the report to develop a matrix of costs by source and task as shown in the chart below.

In the cases studied, all of client costs were related to collection of ESI. Vendors accounted for only about 3 percent of collection costs, while counsel performed about 1 percent.

In the cases studied, all of client costs were related to collection of ESI. Vendors accounted for only about 3 percent of collection costs, while counsel performed about 1 percent.

Vendors performed almost all of the processing, while counsel performed only about 1 percent.

Vendors consumed only about 5 percent of the document review costs, while counsel performed about 68 percent.

When presented in this fashion the significance of the counsel costs and focus on document review is extremely obvious. It also further illustrates the absurdity of focusing on vendor costs or even collection costs as a cost reduction measure. There simply is not that much to cut in either place. Furthermore, vendor costs are spread across all three phases of the effort—collection, processing and document review. Unlike counsel costs, vendor costs are not highly skewed in one area or another.

By contrast counsel costs are highly skewed in the review portion. In fact, more than 68 percent of all ESI production costs are contained within counsel's document review efforts, which on average were more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte of reviewed data.

As explained earlier, a significant reason that counsel costs are so high is their reliance on manual review methods instead of technology assisted review methods. While counsel has attempted various alternatives for reducing the cost of manual document review efforts like lower priced contract attorneys and offshore attorneys, the report explains that all of these have limitations that tend not to materialize any real cost savings.

The answer to achieving real cost savings in e-discovery will come from Technology Assisted Review (TAR). Even organizations like the Sedona Conference have suggested in its various commentary on information retrieval that computerized search methods will be essential with e-discovery. The old manual methods will simply not be practical or feasible.

The Rand Report also examines various alternatives and concludes that automated techniques like predictive coding are the likely answers to performing economic and effective document review. Interestingly, at the top of page XIX of the Rand report, it notes that lawyers have been slow to embrace technology based solutions and suggests that the hesitancy could be based on a reluctance to forgo the historical revenue streams that they have enjoyed performing manual reviews.

If there actually is method to the madness of counsel’s preference for manual document reviews in e-discovery, one might also question the magnitude of both vendor collection and processing costs. If counsel was looking to maximize its document review revenues then it could also have encouraged needlessly expansive discovery and required vendors to collect and process the larger data sets while minimizing vendor services in order to feed the review teams as much data as possible. After all, the average review sets of the cases studied was more than 90 gigabytes while the amount actually produced was only around 23 gigabytes.

Another significant reason that counsel costs are so high could also be the result of their focus on minimizing vendor costs and picking only the lowest priced vendor. The lower price can typically mean fewer services and less value, which in the end leaves more of the work to be done by counsel and typically at a higher rate and using less efficient processes. It is what can be expected when one picks a bicycle over an automobile for solving one's transportation problem, or a shovel over a backhoe for digging a ditch or choosing a sledge hammer over a jack hammer for breaking up concrete. There can be consequences for penny wise and pound foolish decisions.

Summary

Clients are often surprised by what they pay to e-discovery vendors to preserve and process Electronically Stored Information for litigation. Remarkably, that sum is trivial when compared to what they will pay their lawyer for the rest of discovery.

A 2012 study by the Rand Corporation's Institute for Civil Justice reported that, on average, vendors account for only 26 percent of e-discovery costs while outside counsel will consume 70 percent. Even more amazing is that 68 percent of e-discovery costs will be consumed by counsel performing manual document review at an average cost of more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte.

Furthermore, these numbers consider only the cost of producing ESI during discovery. They do not consider other aspects of the litigation like motion practice, summary judgment, mediation, pre-trial hearings or the trial itself. In fact, they do not even consider other aspects of discovery like depositions, discovery disputes, or attending the discovery conference or scheduling conference.

While other industries have employed automated methods to avoid costly manual methods, outside counsel has been slow to embrace computer assisted review methods. According to the Rand Report, a likely reason that counsel has been slow to adopt more efficient and effective document review methods is a desire to maintain historic revenue streams generated by manual review methods.

The reason one hires an e-discovery expert in the first place is not so that counsel or anyone else for that matter can manually review documents at more than 15,000 dollars per gigabyte of which 75 percent are useless. Rather, the reason one hires an e-discovery expert is to use technology to efficiently and effectively solve the disclosure problem of producing ESI. Thus, avoiding e-discovery experts or focusing only on the low priced vendor can be counterproductive.

Modern litigation has a lot in common with auto racing. Just like auto racing is not all about driving, litigation is not all about lawyering.

Modern litigation has a lot in common with auto racing. Just like auto racing is not all about driving, litigation is not all about lawyering.

In auto racing, the owner hires a technical director who designs and builds a car that optimizes the laws of physics, the rules of competition and the race strategy so that the driver can win the race. The same should happen in e-discovery where the owner hires a technology expert that blends digital evidence expertise with rules of evidence, rules of procedure and case strategy so that the lawyer can win the case.

The reality is that there are a lot of ways to lose a race just like there are a lot of ways to lose a case. If one wastes the owner's budget with wasteful car construction, the race team may never hit the track. Even if they do run the race and take the checkered flag, if the costs exceed their benefit it is just losing a different way, at least for the owner.

The truth is that e-discovery can be more effective and more economical than traditional paper based discovery. In fact, the reality is that e-discovery is the big equalizer. No longer is victory determined by the side having the largest army of associates or even the deepest pockets but the one that can best use their technology to defeat their opponent in the courtroom. Unfortunately for many, they have been using their technology more like a club instead of like a machine gun and at great expense to their clients.

Inquiries

Fordham Forensics in Atlanta, GA is a sophisticated provider of e-discovery identification, preservation, processing, data hosting and consulting services.

To learn more about electronic discovery or

discuss a specific matter,

contact us.